It’s hard to imagine a vacuum cleaner that is less human than the Roomba. But it can be if you allow it to have its own mind. Almost immediately after iRobot released its Roomba, a community of autonomous vacuum cleaner enthusiasts began giving their Roombas names and backstories. One of the company’s early TV advertisements highlighted this unlikely bond by featuring people talking about their Roombas like they were people. This is a huge emotional investment for a tool that only exists to collect filth. However, Paolo Pirjanian, the former CTO at iRobot, completely gets it.

Pirjanian says that there is something in our minds that triggers when we witness something move on its’ own. “Our experience tells me that it’s alive and well with a consciousness of its own,” says Pirjanian. Even though we know these machines follow coded instructions, it’s hard not to see agency. These automatons were not designed to make human connections, but to perform a task. This makes our attachment even more extraordinary. What if we could harness our natural empathy for the unexpected and create robots whose job it to connect with humans?

Pirjanian founded Embodied in 2016 with Maja Mataric, a roboticist, to create a better social robot. (Mataric resigned from Embodied in 2018 to concentrate on her research at the University of Southern California. The company opened preorders for Moxie this week. It will ship in the autumn. Moxie, unlike other companion robots such as the household assistant Jibo and the Paro robotic seal, is designed for children. These skills are usually taught to children by their teachers and parents. However, Pirjanian observed that many families need extra support.

He says that studies show that children today are falling behind in their communication, social, emotional and communication skills compared to the previous generation. It could be partly due to too much screen time and social media use, as well as pressures at school which can lead to anxiety and depression. Each child can benefit from improving their emotional and social skills.

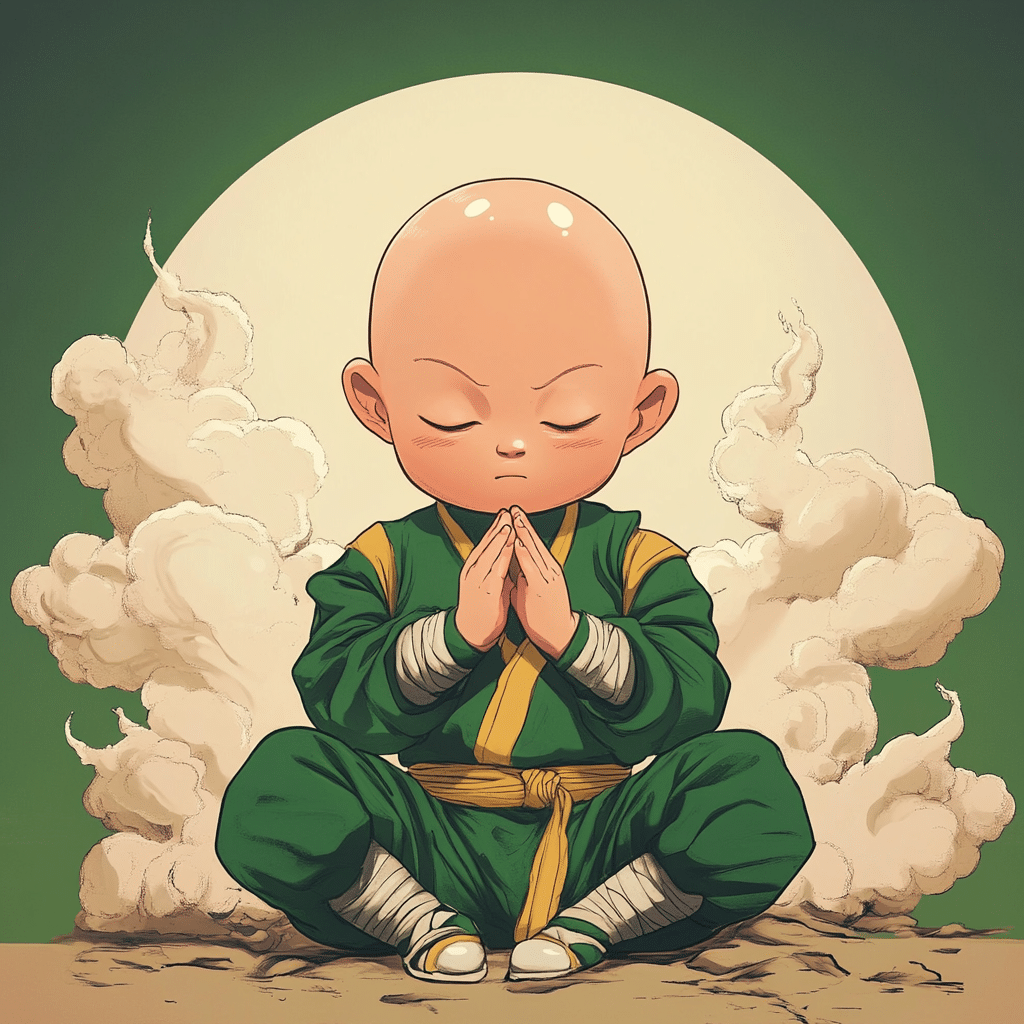

Moxie’s teardrop-shaped head rests upon a baby blue, cylindrical body. It is a hybrid between a videogame and a pet. The main purpose of Moxie is to improve children’s social skills (like eye contact) as well as cognitive skills (like reading comprehension). Moxie is a secret lab robot that has been sent to help children become better friends. Moxie becomes Moxie’s mentor. Pirjanian hopes that the child will help improve their cognitive, emotional, social, and social skills by teaching the robot.

Robots can perform repetitive skills-building tasks that would exhaust a human teacher. Although they can’t replace human interaction, they might be able to augment it. Kate Darling, a researcher at MIT Media Lab who is an expert on human-robot interaction and a research specialist in social robotics, says that there is evidence to support the notion that social robots could help children develop their skills. It is “preliminary evidence” but it is very promising.

Research is showing that companion robots can be especially helpful for children with autism and other neurological disorders. Children with autism, for example, often have difficulty reading facial expressions and eye contact. It helps to practice using robots’ exaggerated emotions. Pirjanian claims Moxie was initially designed for children on the autism spectrum. However, during testing, parents who had neurotypical children were able to use it for their children.

It is difficult to design and build companion robots that are effective despite their promises. Erik Stolterman Bergqvist is a professor of human-computer interaction at the University of Indiana Bloomington. He says that “social robots don’t have an obvious function”. They are designed to be your friend but companionship is a difficult metric. Moxie is very different from robots with a job. You can find the dirt to determine if a Roomba was successful.

Stolterman Bergqvist says, “The problem a lot of designers are having is that once you stop designing things with an obvious purpose it becomes more complicated.” “You are asking, ‘How do people relate?’ They relate in many and varied ways.

Pirjanian and his team relied heavily on artificial intelligence to meet these challenges. Moxie’s head has microphones and cameras. This data is fed to machine-learning algorithms, which allow the robot to have natural conversations, recognize users and look people in the eyes. Moxie’s processor crunches all data, with the exception of Google’s speech-recognition program. As Moxie learns to recognize a child’s face, speech patterns, and developmental needs, the more they interact with Moxie, the it becomes more sophisticated.

Moxie updates weekly with new content that focuses on a theme such as “being kind” and “making mistakes.” The child is then asked to complete thematic missions, reporting back on their experiences. It might ask children to write a note for their parents or find a friend. Pirjanian said that Moxie is a “springboard” for improving social interaction in daily life. He says that Moxie is not meant to be a game-playing platform. Five hours of gaming each day won’t help. “The robot encourages children to go out and practice the skills in the real world. We want them to report back because that’s how we want them to succeed.”

Pirjanian believes that Moxie’s insatiable appetite for data is the key to the robot’s success. The robot can tailor its interactions to each child, and the data is crucial for parents to receive feedback. The robot sleeps, but it also collects data from each day’s interactions, such as the child’s reading comprehension, language use, and time spent on different tasks. The robot sends the data to an app so parents can monitor their child’s progress and track their emotional, cognitive, social and physical development. The robot will also make recommendations over time. Moxie might recommend that parents take their child to a speech therapist if it notices a repetitive verbal tic.

Parents may be hesitant about allowing an internet-connected robot to collect data on their children. While there are many laws that govern how companies can collect data from children, researchers worry that they are not prepared to deal with the flood of personal data (including photos and conversations) that will be generated by social robots. Jason Borenstein, associate Director of the Center for Ethics and Technology (Georgia Tech), says that children are particularly vulnerable because they don’t fully understand the risks of having their data collected. “There needs to be more discussion at all levels about what data children can and should collect when they interact with robots.”

Pirjanian states that Embodied has placed a high priority on data security and privacy in Moxie since its inception. The robot is used by children only if they consent. Most of the data that Moxie collects is done locally on the robot’s computer. Pirjanian says that there was no way we would let images leave the robot. Pirjanian says that only audio data is transmitted over the internet so it can be transcribed using a speech-to-text algorithm. Moxie, which “sleeps”, analyzes the transcriptions and other data of the day and encrypts them before sending them to a parent’s app. Pirjanian claims that Embodied does not have access to the data of any individual child. Embodied only has aggregate anonymized data from all its robots.

Moxie was not just about solving technological problems. Another half of the challenge was to overcome the psychological barriers that human-robot interactions pose. This can be more difficult than teaching a robot to speak. While we readily attribute agency to autonomous machines, there is a limit on how human-like our robots can be. Robots that look too much like humans will cause the same feelings of disgust as the uncanny valley. Users might not be able to form any kind of connection with robots if they are not as similar as us.

Roboticists are still arguing about whether companion robots should be made more human-like. Most roboticists have chosen to limit the use of human characteristics and erred on caution. Robots such as Jibo or ElliQ are more abstract and as faithful to human form as Picasso’s portraits. Robots with eyes and mouths are usually animated on a flat-screen display, detracting from their humanity.

Pirjanian and his coworkers bucked many of the trends with Moxie. Moxie’s teardrop-shaped head features a round screen with two large, cartoonishly animated eyes and a mouth. Moxie is able to make eye contact directly with its user by using machine vision. Pirjanian states that when you place eyes on a robot’s eyes, you have to ensure that they are not creepy. Eye contact is an important part of this.

Moxie cannot move on its own but can tilt its head and bow at the center. Moxie, unlike most companion bots, has two flipper-like arms. These are used to enhance its speech. Based on research in fields such as developmental psychology and animation, each of these design features was carefully selected to foster a relationship between the robot’s user and it.

Moxie is not like the Roomba. Everything about it, from its color to its algorithms to its head, was designed to foster relationships with its users. It might even foster stronger connections between users if it succeeds.